You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

How fast is your internet connection?

- Thread starter Audioseduction

- Start date

ohbythebay

New member

mgalusha

New member

Is mine invisible? Suddenly I cant see it...

Looks like speedtest.net has lost their speed. :roflmao:

dlb2

New member

Are you kidding me? :exciting: I like that "faster than 99% of the US."

NorthStar

New member

Try this one on for size...LOL ..AT work at MSFT

Wow Rob, you wanna trade!? ...I'll give you whatever you ask for!

P.S. No wonder you never post in the hi-def movie and hi-res music threads.

P.P.S. Does this come free with your job?

mgalusha

New member

Try this one on for size...LOL ..AT work at MSFT

Nice. Mine used to look like that as the data center downstairs was also the ISP, as MS is for you. Nothing like a gig connection.

Feanor

Member

How fast can it go? :eyebrow:

Whoa, sucks to be you. :blush:

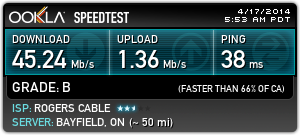

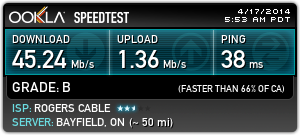

I'm a Rogers subscriber up here in southern Ontario. My results are typical for consumer higher-end service here ...

Attachments

Dizzie

Well-known member

U-verse sucks. In my hood the fiber optic cable ends many blocks from my house and the rest of the run is copper. I just switched from ATT DSL where I consistently got >5mbps on a program where I was supposed to get up to 6.

With my U-verse program (up to 6mbps again) I am now getting 1.12/2.41/1.68 mbps upload in three tests I just finished. High value was Ookla. Low values were Speakeasy. I can't even run E*Trade Pro because the system is too slow.

ATT techs have been working on the problem since Tuesday. I hope they don't think they are done. U-Verse all advertisement but no delivery. I wonder what would happen if I ask to go back to DSL. :reallymad:

With my U-verse program (up to 6mbps again) I am now getting 1.12/2.41/1.68 mbps upload in three tests I just finished. High value was Ookla. Low values were Speakeasy. I can't even run E*Trade Pro because the system is too slow.

ATT techs have been working on the problem since Tuesday. I hope they don't think they are done. U-Verse all advertisement but no delivery. I wonder what would happen if I ask to go back to DSL. :reallymad:

Feanor

Member

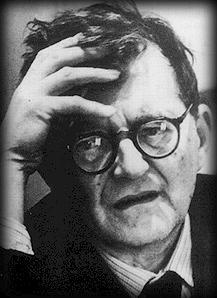

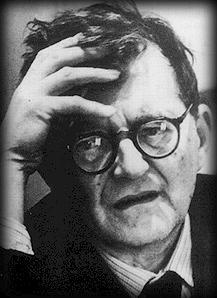

This is for Bill, aka Feanor: I just have to ask, what's up with your avatar? That poor guy looks tired, stressed, anxious, and confused. Here in the shark-tank we're all about the happy face!

Hi, Bob,

Yeah, "tired, stressed, anxious, and confused" is me.

NorthStar

New member

I knew it! ...A great Classical music composer; Shostakovich. ...I luv it!

------

------

MtnHam

Member

Hi, Bob,

Yeah, "tired, stressed, anxious, and confused" is me.Actually that's a picture of Dmitri Shostakovich, one of my favorite composers.

A local FM station played a piece by Shostakovich and the announcer commented that it was written under extreme duress-"He feared for his life!"

From Wikiapedia:

In 1936, Shostakovich fell from official favour. The year began with a series of attacks on him in Pravda, in particular an article entitled, "Muddle Instead of Music". Shostakovich was away on a concert tour in Arkhangelsk when he heard news of the first Pravda article. Two days before the article was published on the evening of 28 January,[SUP][16][/SUP] a friend had advised Shostakovich to attend the Bolshoi Theatre production of Lady Macbeth. When he arrived, he saw that Joseph Stalin and the Politburo were there. In letters written to his friend Ivan Sollertinsky, Shostakovich recounted the horror with which he watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions laughed at the love-making scene between Sergei and Katerina. Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was "white as a sheet" when he went to take his bow after the third act.[SUP][17][/SUP]

The article condemned Lady Macbeth as formalist, "coarse, primitive and vulgar".[SUP][18][/SUP] Consequently, commissions began to fall off, and his income fell by about three quarters. Even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda".[SUP][19][/SUP] Shortly after the "Muddle Instead of Music" article, Pravda published another, "Ballet Falsehood," that criticized Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream. Shostakovich did not expect this second article because the general public and press already accepted this music as "democratic" - that is, tuneful and accessible. However, Pravda criticized The Limpid Stream for incorrectly displaying peasant life on the collective farm.[SUP][20][/SUP]

More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of the composer's friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed: these included his patron Marshal Tukhachevsky (shot months after his arrest); his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks (a distinguished physicist, who was eventually released but died before he got home); his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; shot shortly after his arrest); his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar (sent to a camp in Karaganda); his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova (20 years in camps); his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed).[SUP][21][/SUP] His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; his son Maxim was born two years later.

No wonder he appeared "tired, stressed, anxious, and confused"!

NorthStar

New member

That's very cool Tom.

Would be interesting to identify ourselves to the closest classical composer that we can relate to; overall character wise.

Me; perhaps Frederic Francois Chopin?

Would be interesting to identify ourselves to the closest classical composer that we can relate to; overall character wise.

Me; perhaps Frederic Francois Chopin?

Feanor

Member

A local FM station played a piece by Shostakovich and the announcer commented that it was written under extreme duress-"He feared for his life!"

From Wikiapedia:

In 1936, Shostakovich fell from official favour. The year began with a series of attacks on him in Pravda, in particular an article entitled, "Muddle Instead of Music". Shostakovich was away on a concert tour in Arkhangelsk when he heard news of the first Pravda article. Two days before the article was published on the evening of 28 January,[SUP][16][/SUP] a friend had advised Shostakovich to attend the Bolshoi Theatre production of Lady Macbeth. When he arrived, he saw that Joseph Stalin and the Politburo were there. In letters written to his friend Ivan Sollertinsky, Shostakovich recounted the horror with which he watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions laughed at the love-making scene between Sergei and Katerina. Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was "white as a sheet" when he went to take his bow after the third act.[SUP][17][/SUP]

The article condemned Lady Macbeth as formalist, "coarse, primitive and vulgar".[SUP][18][/SUP] Consequently, commissions began to fall off, and his income fell by about three quarters. Even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda".[SUP][19][/SUP] Shortly after the "Muddle Instead of Music" article, Pravda published another, "Ballet Falsehood," that criticized Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream. Shostakovich did not expect this second article because the general public and press already accepted this music as "democratic" - that is, tuneful and accessible. However, Pravda criticized The Limpid Stream for incorrectly displaying peasant life on the collective farm.[SUP][20][/SUP]

More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of the composer's friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed: these included his patron Marshal Tukhachevsky (shot months after his arrest); his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks (a distinguished physicist, who was eventually released but died before he got home); his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; shot shortly after his arrest); his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar (sent to a camp in Karaganda); his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova (20 years in camps); his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed).[SUP][21][/SUP] His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; his son Maxim was born two years later.

No wonder he appeared "tired, stressed, anxious, and confused"!

There were multiple occasions in Shostakovich' career in the Soviet Union when he literally feared for his life, and he was out of favor and isolated from official cultural participation for several in addition. He is one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, (and that's saying a lot).

NorthStar

New member

My great, great uncle was Antonin Dvorak!

Truly Bob!

Bobvin

Active member

- Joined

- Jun 25, 2013

- Messages

- 1,068

Yep, no shit. When we were bike riding last year from Prague to Vienna I almost went through the village of my great grandparents, but the flooding closed the roads. We were disappointed to have missed it. But in Prague Dvorak is KING!

Re: Shostakovich... I like his music. It is sad so many great artist lead tortured lives. But sadly much art comes from pain.

Re: Shostakovich... I like his music. It is sad so many great artist lead tortured lives. But sadly much art comes from pain.

NorthStar

New member

True; true artists are the ones who suffer(ed) the most.

* Great great uncle, Dvorak; we are back now to which years? ...Eighteen something?

It's fun to know/discover our ancestors. ...And from way way way back.

Then we'd realize that we're all coming from the same hadron collider (black hole, or the big bang).

__________________

=> My Internet speed is so slow that I cannot go back in time fast enough to reach the other side of that black hole.

* Great great uncle, Dvorak; we are back now to which years? ...Eighteen something?

It's fun to know/discover our ancestors. ...And from way way way back.

Then we'd realize that we're all coming from the same hadron collider (black hole, or the big bang).

__________________

=> My Internet speed is so slow that I cannot go back in time fast enough to reach the other side of that black hole.

NorthStar

New member

That's a nice name; Jelinek. ...Antonin, born in 1841, and died @ 63, one hundred and ten years ago.

Bob, do you believe in the blood line, in the genes, in the aura? ...I do.

Bob, do you believe in the blood line, in the genes, in the aura? ...I do.